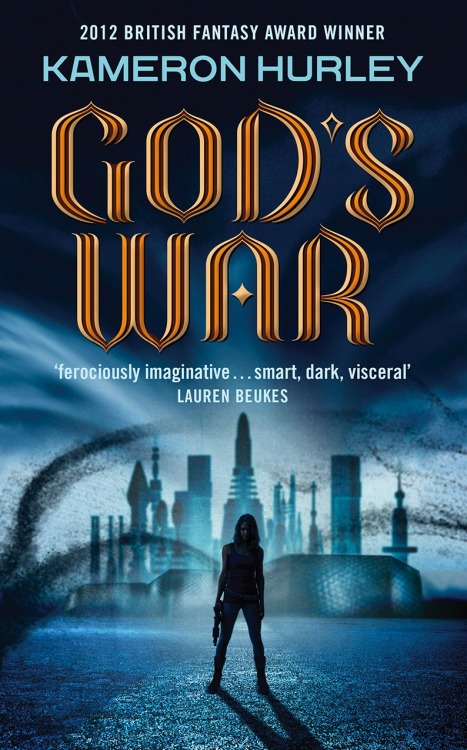

If you’re

interested in fantasy and science-fiction then you’ll probably want to read

Kameron Hurley’s God’s War. In a

comment on Maureen Kincaid Speller’s review,

Niall Harrison (editor of Strange Horizons) wrote:

I think you're

right to peg it as a zeitgeist novel: I read it about a year ago now, and it

hit me square between the eyes because it did everything I'd been wanting a sf

novel to do in one go. It was generically fluid (in dialogue with many

different parts of the field, I think), rampantly intersectional, unashamedly

ambitious yet also (it seemed to me) solidly commercial. It felt to me like a

book that lots of different types of reader would respond to, and that would

expand the kinds of discussion lots of readers would have about sf.

Harrison championed the book when it came

out in 2011 (in the US) and now, with a UK release last May, it has been

shortlisted for the BSFA Award and

the Clarke Award. It also won the

2011 Kitschies Golden Tentacle for

best debut novel. That said it has also come in for a fair amount of criticism

too. Dan Hartland provides links to much of the debate here

and I would urge any reader to follow the discussion when you sit down to

consider the book. There are also blog posts with Hurley here,

here

and here.

Nyx is a Bel Dame, a woman employed by her

country Nasheen to retrieve and mercilessly kill deserters from their war with

Chenja. These two nations, the largest on the planet of Umaya though other

smaller nations exist and we meet characters from there too, have been at war

for centuries so the people know no other way of living. Violence at every

level of society is endemic. With all the men fighting at the front, Nasheen has

become a matriarchal society. Women do all the jobs, most of their sexual

relationships are lesbian; some are bisexual. The novel follows a complex plot.

A short prologue sees Nyx lose her Bel Dame licence and go to prison for doing

illegal work. Out of prison she has gathered a team of misfits and immigrants

to help her do bounty work before being hired by the Queen of Nasheen to find

and retrieve an alien, from the planet of New Kinaan, who has gone missing.

This central plot sees Nyx’s team pulled in all directions as various factions

in the Nasheenian ruling class fight for alien technology.

Nyx is a Bel Dame, a woman employed by her

country Nasheen to retrieve and mercilessly kill deserters from their war with

Chenja. These two nations, the largest on the planet of Umaya though other

smaller nations exist and we meet characters from there too, have been at war

for centuries so the people know no other way of living. Violence at every

level of society is endemic. With all the men fighting at the front, Nasheen has

become a matriarchal society. Women do all the jobs, most of their sexual

relationships are lesbian; some are bisexual. The novel follows a complex plot.

A short prologue sees Nyx lose her Bel Dame licence and go to prison for doing

illegal work. Out of prison she has gathered a team of misfits and immigrants

to help her do bounty work before being hired by the Queen of Nasheen to find

and retrieve an alien, from the planet of New Kinaan, who has gone missing.

This central plot sees Nyx’s team pulled in all directions as various factions

in the Nasheenian ruling class fight for alien technology.

Above all God’s War is ambitious. In Nasheen we have a matriarchal society that

is just as violent, corrupt and foul as any society dominated by men. Kameron

takes on the argument that any society dominated by women would somehow be

fairer, more egalitarian or different in crucial ways. On Umaya it’s the larger

social, political and economic structures that shape behaviour as they do under capitalism. This also has a crucial twist. Sexual relationships and desire are

also mediated by the way Nasheen has developed. This is the best part of the

novel and, even considered alone would make God’s War an impressive achievement. This is Hurley describing what

she has done:

Writing the character of Nyx – a bisexual bounty hunter with the brute

sensibilities of Conan and grim optimism of a lottery junkie – was the first

time I tackled writing a character who explicitly desired folks of either sex.

What she desired in folks tended to vary, but in general she found the

too-pretty and the plainly ugly equally fascinating: the pretty because they

seemed out of place on a toxic, contaminated world, and the ugly because it

showed a degree of resilience; she liked to think she could see stories in

their faces.

Communicating that should have been easy. I am, after all, not the

straightest arrow in the quiver, myself. But for some reason I found it

necessary to make her desires really, really clear, and my clumsy authorial

attempt stood out like a raised thumbprint on the page. LOOK HERE SEE THIS SHE

LIKES DUDES AND GALS LOOK LOOK.

The reality was, I was writing with a straight white male gaze in mind.

I was writing with the idea that her desire was somehow other, something that

had to be explained to a reader who viewed straight as default. By pointing so

loudly at her desire, I was automatically flagging it as something out of the

ordinary.

But I was writing about a world that viewed bisexual and lesbian women

as default, and that needed to come across in everything I wrote – from the way

people non-react (and, in truth, expect) that women are married to or have

female lovers – to the way they talk about love and desire and sex.

I had to rebuild the default narrative of “assume everyone’s only

attracted to people of the opposite biological sex” (and the assumption that

intersex and trans folks don’t exist) from the ground up.

Obviously, that expected default is a lie. It’s always been a lie. But readers carry it. Writers carry it. Society carries it. Challenging it is a monumental task.

Obviously, that expected default is a lie. It’s always been a lie. But readers carry it. Writers carry it. Society carries it. Challenging it is a monumental task.

For starters, it meant rubbing out additional lines of narrative that told readers Nyx was bisexual,

because to be honest, in this world there wasn’t really a box like that. If

strong female desire, and strong desire for other women, was the norm, it

wouldn’t need to be said.

Think of it this way. If I had a man looking at a woman in a story and

thinking about how much he’d like to go to bed with her, I wouldn’t then say,

“In Menscountry, it was natural for a man to desire a woman like this one. They

may even go through a short courtship period leading to a monogamous marriage,

a sort of commitment ceremony which often includes family and friends to

witness the event.”

No. I’d just note the attraction. End of story.

The cool thing about narrative is that the longer you’re immersed in

that narrative, the more normal it becomes for you as a writer (and, hopefully,

as a reader). Because the society I’d built sent all its men off to war, the

culture and its expectations had shifted. From a narrative standpoint, I wanted

to build up a whole world where “woman” was default, and women have automatic

privilege, but do it in a way that felt organic to the story, while at the same

time deconstructing ideas around default sexuality.

That

Hurley gets this right attests to a serious and successful act of world-building (and an accompaning attention

to detail). Indeed the world-building for most of the novel is convincing and

effective. There are no horrible info dumps and you have to work hard, in a pleasurable

way, to make sense of the world. In the latter third this breaks down a little

as the narrative becomes a little clumsy, explaining plot details and

motivations via characters thoughts. Indeed the writing is uneven throughout.

It’s never clichéd but nor is it rarely more than competent; the gritty,

hard-boiled style only occasionally bursts into life. In retrospect you

remember that the greats of the hard-boiled style, say Chandler or Paretsky,

always wrote in the first person. Hurley’s choice of the limited third person

makes it harder for her to convey some of that noirish style and humour but, to

be fair, she’s using the style to achieve some of the same effects of authors

like George R R Martin and Joe Abercrombie. Indeed a comparison with

Abercrombie is actually quite useful. God’s

War, more than anything else reminded me of The First Law trilogy. Like Abercrombie, Hurley makes you want to

follow immoral, often detestable characters; you want to understand them, hope

that they might do better but understand when they fail, pulled back into the

hard choices, and chaos, of their inhospitable worlds. Abercrombie, in his use

of the third person limited and in terms of nuance, subtlety and structure has

got better and better with each subsequent novel and by all accounts Hurley’s

style improves in the other sections of her trilogy. Crucially Abercrombie also

failed somewhat in his portrayal of the Gurkish in those novels and I think

this is where Hurley makes the most important mistakes.

The

planet of Umaya is dominated by two versions of Islam. The war it seems started

over disagreements about scripture and faith and now Nasheen and Chenja have very

different cultures. Nasheen, dominated by women is much more recognizably western

in its attitudes toward religion. Thus its citizens can choose how and when to

pray though many do not. Religion is still present in everyday rituals and

ceremonies but it doesn’t dominate ideology or their way of life. Chenja is

presented as much closer to twenty-first century conservative versions (and conceptions) of

Islam. Thus men dominate and women are subservient; religion dominates

ideologically and reaches into every area of life. Most of the novel is seen through

Nyx’s eyes and occurs in Nasheen which means that in terms of the novel Nasheen

is the norm. Hurley tries to complicate our perception by including Rhys, a

Chenjan exile as the secondary character and by making him complex and sympathetic.

Nonetheless he most definitely is a secondary voice in the hierarchy of voices that

inhabit the novel. Unfortunately the effect is to ‘other’ Chenja and so reinforce

Western stereotypes about Islam – more male ideologues who oppress women,

whilst also reinforcing the current liberal promotion of atheism. Of course BOTH

societies are seen to be oppressive and hypocritical but the text doesn’t work

sufficiently to undermine or defamilarise the awful and hysterical anti-Muslim

feeling that dominates much public discourse in the West.

Like

other commentators I also don’t think I really believe in the world Hurley has created.

The idea of a world continually at war isn’t new. I remember loving Rogue Trooper in 2000AD where the Norts and Southers are in perpetual war but I didn’t

really think about the consequences back then! It’s not just the logistics that

I think unlikely – producing enough men for the battle, and, how on earth does

Chenja manage to function at all (?), but it seems to me the fabric of society wouldn’t

be able to survive. Without the bonds of love and affection that bind us I

suspect society would break down into barbarism. It’s one of the interesting

tensions in the novel that Hurley can’t control. Few characters seem to have

long lasting relationships – trust, love and friendship are all too fragile. In

the novel everything is forever breaking down. On a societal basis that would

have had a cumulative effect long ago.

Part of the joy of speculative fiction is to

make you think and God’s War has

certainly done that (and there’s more in the novel to think on and dissect than

I’ve covered here). In that respect and in terms of its sexual politics it is

successful. I think the Kitschies

got it about right – it’s a good debut novel but it gets too much wrong to

compete with Smythe and Priest on the two shortlists. I think I also enjoyed Ancillary Justice more. That said I

liked the grit and the the grim of the novel, and I liked Nyx and her relationship with Rhys and the other members of her team. I’ll

still be recommending it to friends and I already have a copy for the 6th

form library. I'm looking forward to see what they’ll make of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment