Wednesday 27 January 2016

Europe at Midnight.....or 'A Mundt in the Country' - Dave Hutchinson

The short review is this: read it - it's a fascinating page-turner that will get you thinking in all kinds of ways. What follows is a much longer discussion and contains spoilers with lots of quotes.

John le Carré had this to say on the 50th anniversary of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold:

"The novel’s merit, then – or its offence, depending where you stood – was not that it was authentic, but that it was credible. The bad dream turned out to be one that a lot of people in the world were sharing, since it asked the same old question that we are asking ourselves fifty years later: how far can we go in the rightful defence of our Western values, without abandoning them along the way? My fictional chief of the British Service – I called him Control – had no doubt of the answer: ‘I mean, you can’t be less ruthless than the opposition simply because your government’s policy is benevolent, can you now?’

Today, the same man, with better teeth and hair and a much smarter suit, can be heard explaining away the catastrophic illegal war in Iraq, or justifying medieval torture techniques as the preferred means of interrogation in the twenty-first century, or defending the inalienable right of closet psychopaths to bear semi-automatic weapons, and the use of unmanned drones as a risk-free method of assassinating one’s perceived enemies and anybody who has the bad luck to be standing near them. Or, as a loyal servant of his corporation, assuring us that smoking is harmless to the health of the Third World, and great banks are there to serve the public. What have I learnt over the last fifty years? Come to think of it, not much. Just that the morals of the secret world are very like our own."

Le Carre's novel has faults - caricature, tacit homophobia and sexism, but it's still a great text: discursive, savage and poignant with a sharp, sinewy energy and intensity. His question, if not the answer, has faults too: whilst I believe that democracy is preferable to Stalinism, dictatorships and autocracies I don't believe that the UK's policies, especially its foreign policies have ever been benevolent and nor do I believe in Western values much beyond greed and imperialism. Yet I decided to read le Carré straight after I'd finished Europe at Midnight, not to compare quality but to help me think about the portrayal of Hutchinson's two main protagonists and the metaphorical and discursive richness of the novel. This may seem a little perverse - I can only say that I found the first reading of Europe at Midnight exciting and thought-provoking - it's much faster to read than its predecessor, more plot driven I think - but ultimately a little unsatisfactory. Yet since I admired Europe in Autumn so much and with many of my favourite authors and critics heralding Midnight as one of the best books of 2015 I felt I needed to further untangle what I was thinking and feeling. And it seemed that le Carré's pessimism, and his questions, would help. Also, I wanted to do the Mundt pun!

[Mundt is the name of characters in both novels]

"What do you think spies are: priests, saints and martyrs? They’re a squalid procession of vain fools, traitors, too, yes; pansies, sadists and drunkards, people who play cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten lives." (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold: p). In Midnight in Europe the two main protagonists are spies of a sort but neither fits the description in le Carre's great novel. One is Rupert, the Professor of Intelligence in a state that has just had a revolution. In the aftermath their organisations are still bureaucratic and individualistic - it seems they learned little from organising collectively to overthrow the previous regime. It is a very middle class kind of revolution with a 'New Board' replacing the 'Old Board'. His situation is precarious: counter-revolution is still a serious possibility and they "were all finding Democracy more difficult than we’d imagined" (loc 183); “The Revolution’s over, for fuck’s sake. We won. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.” (loc 777) . The regime they have overturned will remind the reader of the Nazis and other genocidal regimes - there are mass graves and human experimentation. Furthermore the perimeter of their territory is booby-trapped with all manner of killing devices - no one can escape. We think it might be a nation trapped by geography but we'll learn it is, rather, a state trapped by geography, history, politics and Imperialism.

Rupert is, according to Araminta, a secondary character we trust, a "good soul" and his first person narrative is full of engaging detail and light comedy. We are supposed to like him. The reader will empathise with his attempts to do the right thing under difficult circumstances. That sympathy will be tested however as Rupert succumbs to irrational decisions and brutality. He wonders for instance: "It would, I ventured wearily at one meeting, be just as effective if we simply lined everyone we didn’t like up against a wall and shot them without going through any legal formalities first." (loc 1715). Worse, he becomes frustrated when questioning one of the Old Board and fakes shooting him - a form of torture. Now Araminta decides to have some time away from Rupert and asks “I want to decide whether you’re worth the trouble,” (loc 967). This is a crucial question for the text I think. The text, full of mystery and questions, wants to take you for a ride and it's easy to let yourself get caught up in the excitement. What and where is the Campus? Who is Araminta? Where did the Old Board get their scientific expertise? Along the way it's easy to tacitly accept Rupert's worldview. Later in the novel Rupert will become a spy for the British under, it has to said, extraordinary circumstances and it's in this second half of the novel that I was most reminded of Europe in Autumn, as he gets lost in plot, detail and survival. The reader might find it hard however to have sympathy for the degree to which he sells out. Or they might not.

Back in the 'real' world - a slightly future Europe fracturing into various mini states, we find the other main character, Jim, a reasonable man; a relatively low ranking intelligence officer drawn into a peculiar situation, and promotion, somewhat by chance. In London a 'Maze of Steel' has replaced the Ring of Steel due to terrorist bombings and increasing security and surveillance concerns. He must investigate the stabbing of an unknown man. In this section, again, Hutchinson uses various techniques found in police procedurals and thrillers so that we are continually asking ourselves what is significant: there are lots of details that are important for good storytelling but might not be significant in terms of solving the mysteries we encounter. Again, Hutchinson wants us to like Jim - he is a decent sort of chap, sensitive to others' stupidity and unpleasantness.

There are many good things about Europe at Midnight. One of Rupert's colleagues is responsible for investigating the horrors of the Old Board: "Harry had been brought face to face in the most basic way with the madness the Old Board had embraced, and some of it defied rational explanation." But of course history teaches us there are plenty of explanations for the atrocities various regimes, and big business, commit, and we understand too that Western governments and regional powers support violent regimes around the world if they think it expedient in preserving resources or geopolitical control. This is the horror of the Campus. It's that idea taken to its logical conclusion. A small fascistic playground where all kinds of inhuman research can take place away from prying eyes. Though let's not kid ourselves. US and UK governments give open support to states that will help them with their dirty work again and again: the Indonesian regime in the 1960s, or Pinochet in the 1970s or Saddam Hussein's regime in the 1980s and so on, and on - any of these would be considered horrific too, by anyone vaguely sane. Instead the Kissengers of this world get the Nobel Peace prize.

The text is also skilful at misdirection and is full of narrative choices that you have to make sense of: why several pages of a police interrogation but a genocide revealed in a sentence? Why one section in first person and the other in third? For the most part the reader is expected to trust the appraisals of the narrator in Jim's sections: "He had the look of a ‘flier,’ an officer bound for greater things. Ferris, on the other hand, had the calm, rumpled, professional look of a copper who had pounded many miles of pavement, had perhaps been passed over for promotion once, accepted it as his lot, and quietly got on with doing his job." (loc 1277) This has the effect again of asking us to trust what we are being told. And there's this: '“Narrative,” Baines had told me. “Always narrative. They will want to know everything, and by the time they know everything they have to trust you.”' (loc 3474) - it's almost as if Hutchinson is giving us a clue to his own games.

Furthermore the novel plays with genre and stands in a great tradition of subversive thrillers. There's a point where Rupert has to face up to the death of his colleagues: "Investigating a murder looks easy in the books. You have a number of suspects, you keep your eyes open, you assemble all the evidence, you find your killer. It’s not like that in real life. Real life is horrifically complicated and you can never be sure that you have all the information you need, or even whether what you have is in the right order. You start with what you know –fact: two dead women –and work outwards, but did you miss something? Does someone you haven’t thought to talk to have some vital piece of the jigsaw? Is the murderer here in this very room with you?" (loc 1869). This summing up seems entirely reasonable but will prove to be heroically short of the mark: the truth is beyond the bounds of his experience and yet coarse and quotidian all the same. You'll have seen it before in other great thrillers - think Chinatown perhaps - the moment when the protagonist finally understands their inability to imagine what other human beings will do for power, profit and gratification, and the networks and structures that facilitate it.

It is rich in satire and irony: Rupert reflects on his life in the Campus: "I had come from a world where everyone was white, no one had to pay for anything, and there were no gods. All our books had been rewritten and edited so that we had no idea that this other world existed. We all spoke the same language. Compared to this place, my home was a pale, insipid thing, and I came to hate whoever had condemned my people to that." (loc 2654) Think North Korea mixed with Cold War Eastern Europe and Tolkein's The Shire.

Best of all Hutchinson evokes a world of borders and zones, crossing points and palimpsests that is richly metaphorical. It's about the world we seem to remake again and again - where it's more important to keep people out than welcome them in; where we twist ourselves in absurd knots to justify any horror - a world of paranoia and stupidity.

So what made me unsure?

In a recent review of le Carre's biography William Boyd quotes the author and goes on to hypothesise about our fascination with spies:

'“I think all of us live partly in a clandestine situation . . . We hardly know ourselves – nine-tenths of ourselves are below the level of the water.”

'The tropes of espionage – duplicity, betrayal, disguise, clandestinity, secret knowledge, the bluff, the double bluff, unknowingness, bafflement, shifting identity – are no more than the tropes of the life that every human being lives. The fully achieved, sophisticated espionage novel works precisely because in it you find all the troubling complexities of our own lives writ large. We all lie, we all pretend, we all betray – but in the spy novel you see those fundamental aspects of human behaviour, the human predicament, under a magnifying glass. The consequences may be more cataclysmic – walls may come down, bombs explode, deaths occur – but they find their exact and pertinent echo in our own quotidian experience.' (William Boyd in The New Statesman 21/10/15)

I'm happy to agree to most of that but for the best writers spy novels show us exceedingly intelligent people unwilling, or unable, to question the vacuous certainties and ideologies of nation states. Or else they get caught up in the madness and duplicity of the game, mired in complexity and paradox. They'll put up with all manner of violence, torture, murder and mayhem to 'protect' their country, or, rather, to further the interests of the ruling class at any cost. In any rational world they would be figures of vilification and satire, but here on planet Earth they are too often figures of romance and daring - and don't get me wrong, I love the odd Bond (or Bourne) film as much as anyone else. Also we have to feel a degree of empathy for the protagonists so that we want to keep on reading, even if the text will reveal the squalid greed and stupidity at the heart of their enterprise. Somehow le Carré manages this time and again. Does Hutchinson? Moreover as readers, we have to separate out the worldview of characters from the worldview of the text and sometimes that can be tricky, often pleasingly so.

"One of the secrets of intelligence work is to let the other party do as much of the work as possible. You set up the conditions and let events take their course, and when it’s all over you have whatever it is that you need. That’s the theory, anyway." (loc 5444). This seems a pretty good description of how Hutchinson has set up his novels. I wasn't entirely sure I liked Rudi in Europe in Autumn just as I'm even more sure that I don't like Rupert: "I wanted to punish the people who had destroyed my world, to punish them hard, bring their own world down around their ears. And I knew that was hopeless. Unless I ever got my hands on one of these nuclear weapons, there was nothing I could do." (loc 5557) Can you forgive these thoughts as normal when someone has lost so much and seen such injustice or do you see them as the thoughts of a person lost in the game he is pursuing and perhaps too, lost to humanity. Rupert remains a deeply conservative man: "It seemed perfectly reasonable to me that a group might want to set up its own nation, if it had the means to do so, and whoever had created the Neustadt had certainly not been without means." (loc 4005) Even for someone still learning about European history this seems wilfully ignorant. Without collective organisation it would end up creating all the same problems as before. This state in particular: "the world’s biggest data haven, the world’s biggest private bank. Like a fortified version of Switzerland." (loc 4022), probably "the third richest nation on Earth. It’s basically the place where Russian billionaires keep all their money and their secrets" (loc 4041) AND with a wall constructed in a similar way to the Berlin Wall. No one wants to learn the lessons of history or rather the "oligarchs" know all too well what they are doing. Once again it's hard to determine exactly what the text is doing. There is a joke here after all, since at the moment many Russian billionaires hide their money in London but it feels like the horror and the absurdity are pushed away onto others.

Moreover there are sections that are particularly difficult to parse, like the one where Rupert, acting as a spy for the Community's Intelligence Service, visits a village of fishermen and women intending to "withdraw their labour". Here he speaks to Horace, in what is for me is one of the key scenes in the text and it repays close reading. Because Rupert is the main character and you often see his rationality and his Everyman thinking it would be all too easy to go along with what happens and accept his views in this passage. What worries me about this scene and the novel as a whole is that instead of being a text that provokes questions about the nature of things it is a text that will confirm individual readers in their worldview. The scene reminded me of another remark earlier in the novel by Araminta when considering prospects in the Campus: “Your people are starving, Rupe. They’ll follow anybody who promises them a square meal. I’m sorry. It’s fine banging on about freedom and dignity when you’ve got a full stomach. If you’re hoping for a popular uprising, forget it; that train isn’t coming.” (loc 2443) This is again, good, bourgeois common sense but hardly tells the truth of revolutions down the ages.

The other facet that I can't quite accept is the worldbuilding: "It seemed to go on as far as the eye could see, a pleasing arrangement of lawns and trees and bushes and fountains. The whole Community was like that, even the parts that had been allowed to grow wild. There was no magic here, no wizards or dragons or unicorns. It was just a country full of quiet people ruled by pencil-pushers. They lived for the status quo, the quiet life. They just wanted to be left alone. Europe had nothing to fear from them." (loc 6059) This I think is Hutchinson satirising the little Englanders' dream of a white, rural England, but a couple of pages before Rupert had thought slightly differently: "The Directorate was also very good at its job. It had sources in every area of private and public life, kept a watch on everything, and was prepared to move quickly – but calmly – to nip trouble in the bud before it got out of hand. After two centuries, these factors had combined to produce a populace which was too polite to protest or oppose, on the whole. The Presiding Authority was stern but avuncular, and so long as it continued to give the people what they wanted nothing was going to change. The people of the Community were, with a few exceptions, sheep. Sheep with nuclear weapons." (loc 5954) And it's passages like these that worry at me. Two centuries is a long time, even in the bloody Shire. I guess I don't believe it. I don't believe that the ruling class have it this worked out, I don't believe all kinds of contradictions wouldn't bite them in the ass, I don't believe that a populace faced with contradictions, just like Horace, wouldn't find ways of learning and organising.

And then there's this: at the end of the novel Jim sums up their powerlessness: '“Adele once told me that the problem with people like us is that we only ever see parts of the story,” he said. “Or we see it from odd angles and perspectives. We very rarely see the whole picture. There’s a story – I don’t know whether it’s true or not – that during the Second World War Polish women used to collect old used cleaning rags from the German armoured regiments that had occupied their country. The rags were then sent off for analysis by the Polish resistance and the viscosity of the oil on them was tested. You see, you need different viscosities of oil for different weather conditions. The theory was that a sudden change would signal preparations for a German invasion of Russia......We’re like those old Polish women,” he went on. “Collecting rags, never knowing what the results of the analysis are.”' (loc 6466) A little part of me believes that but for the most part I'd rather bestow my empathy on more deserving fellows. And maybe Hutchinson is all too aware that it's just another narrative they tell themselves to live with their foolishness, lies and deceit.

The 21st century has already seen a number of revolutions throughout the Middle East and elsewhere. It has seen unprecedented mass protests and demonstrations too. Yet all of those movements and moments of hope have encountered reaction and violence. Everywhere right wing movements and governments of various stripes, in partnership with big business, are growing ever more reactionary and seem to be prevailing. It would be easy to feel desperate, miserable and cynical during such a time but of course I'm sure there were various moments throughout the twentieth century when most people thought the end of the world was very close, especially during the two world wars and the tense moments of the Cold War. And it could also be argued that more people have more food, freedom, health care and education than ever before and thus pessimism is objectively an incorrect outlook. Still, when you factor in growing inequality, the ubiquity of war and economic crisis, the growing threat to democracy from increasing surveillance and the various strategies western governments (and their proxies around the world) are putting in place with their 'Global War on Terror', AND the consequences of climate change, then, I think it's a reasonable conclusion to see the clouds of DOOM gathering over all of us. This is a world where many Labour MPs voted to bomb Iraq because, however inane and unjust, they understood the vote was about the UK's standing in the world, its reputation as one of the world's enforcers: a bully to be relied upon by the other bullies. This is a world where nation states are seizing the assets of refugees. Inhumanity and absurdity abound - perhaps they always have. In other words pessimism is fairly realistic at the moment.

Europe in Autumn was brilliant at imagining a near future Europe fracturing into smaller and smaller nation states after a flu pandemic, economic crisis and further climate crises had caused. This was a novel that explored the stupidity of nationalism and the pettiness of borders and those that guard them. Europe at Midnight goes further to think about the machinations of Imperialism and all the intrigues going on behind the scenes: "I thought of what my home had become, what generations of Committees and unknown Europeans had turned it into. That wasn’t real life. It was a joke, a parody of self-determination. I didn’t belong anywhere, and certainly not here, where everyone was polite and nice and prepared to use biological weapons and nuclear bombs at the drop of a hat." (loc 6165). This is a picture of Imperialism and of the ruling class firmly in control even as they scrabble amongst themselves for power.

At the end Rupert has a final assessment of what has been going on: 'My home and everyone I knew, gone. Tens of millions dead in Europe. I’d been wrong about the Community. They were not remotely harmless. And worse, they seemed to be playing some kind of game with someone else who was also not remotely harmless; we’d been caught in the middle for years, without knowing.' (loc 6207) and '“Listen, I made the mistake of thinking they were a bunch of dull bureaucrats living in some kind of fantasy England, and they’re not. They’re very dangerous. They killed everyone in the Campus to stop the flu spreading across the border. The people who are running things over there now are a bit more progressive than before, but they’re still dangerous. They want security and they think they can only get that by running everything.”' (loc 6400) This is a world of competing bastards and fools believing they can control what goes on.

So it's not pessimism that gives me doubts about the novel, it's more that I can't escape the feeling that there is ideology hiding out in Autumn at Midnight, quietly reinforcing some rather middle class formulations and ideas - rather than the straight story open to interpretation and investigation that Hutchinson might want. It feels like the text wants us to believe the ruling class have more control than they do. I'm happy to admit I might be wrong. It's easy to get confused when you're debating with yourself! And indeed I wish I had someone to debate with. For all that, this is the first novel I've reread immediately for AGES. That in itself should be a huge recommendation. This is the kind of political, genre defying sci-fi that we need

Thursday 14 January 2016

Rereading Brooklyn

[Includes spoilers]

I remember loving Colm Toibin's Brooklyn the first time I read it (in early 2010 I think, when it won the Costa Prize). I also thought last year's film adaption was fantastic. I was sorry then that thirty pages in to my reread I felt underwhelmed. It was the familiarity of the story and the simplicity of style and structure that did it: no beautiful prose, no irony, no oomph. That said I'm happy that I stuck with it as many of the the virtues I enjoyed the first time were still satisfying and I discovered more too.

It's easy to admire Toibyn's precise tightly controlled prose - simple but completely free of cliche. The third-person narrative voice is perhaps somewhat peculiar. It describes everything from the point of Eilis Lacey, a young woman growing up in 1950s Ireland, sent to New York for a new life, but it does so without free indirect speech, instead describing Eilis's observations, actions and ideas with spareness and exactitude. The effect is to convey her seriousness and her methods of thinking. If I didn't fully appreciate this aspect of the text on a first reading it was because I was enjoying the close proximity to Eilis's thoughts and feelings and how it gives us access to her empathy and kindness. I loved the pleasure of witnessing her subtle and understated journey of discovery and Toibyn's astuteness, psychological understanding and wisdom. Seeing Eilis carefully consider her options and become braver was lovely to see.

On second reading I was able to appreciate the quietness and precision of tone more fully and this allowed me to see Eilis's passivity. Eilis's fate is often decided by others and by chance. She has few options but goes about her life with admirable determination and delicacy. Toibin's meticulousness in showing her ways of seeing mean that you trust in her character: in the decisions she makes and her estimations of others. This is crucial to achieving a different kind of complexity in the second half of the novel.

In plotting her return to Ireland, Toibin shows the reader how, habit, environment and circumstance shape Eilis's thoughts and decisions: "It occurred to her, as she walked down the aisle with Jim and her mother and joined the well-wishers outside the church, where the weather had brightened, that she was sure that she did not love Tony now. He seemed part of a dream from which she had woken with considerable force some time before, and in this waking time his presence, once so solid, lacked any substance or form" (245). What I first saw with understanding and admiration - Eilis's openness to experience life on her return to Ireland and her romance with Jim, now touches me with a little pinprick of horror and compelling force. To be so sure that she she does not love Tony after she and the reader are so thoroughly convinced of her happiness fifty pages previously is quite a turnaround. Toibin's method, to draw us so close to Eilis so that we trust her view of the world, and to show her as anything but fickle throughout the rest of the novel, now underscores this difficult truth about the seductive ease of routine and day to day existence. It asks us to sympathise too with Eilis's limited experience of life and with the joy of finding sympathy and love with others.

With all that said, this is hardly a revelatory truth, and nor is there much else in the novel that would make me want to read it again. I prefer a writing style with more energy and a structure that poses more questions. Furthermore there is one aspect that vaguely annoys me. Throughout Toibin asks us to see others through Eilis' eyes AND to trust her judgement. She is constantly imagining what others are thinking and feeling but, unless I am missing the obvious, the text provides no signs that she might be wrong. This is a little bit weird and rather unsatisfactory. Structurally it makes us believe in Eilis's sensitivity and in the story she is constructing about her life but more importantly it reinforces that deeply ideological sentiment that we can understand others so simply and completely. And also, isn't it all a bit too nice and safe? I wanted a bit of peril or irony maybe.

So, definitely glad that I read it again, because it forced me to look more closely, and it's still a novel that I will recommend and think of fondly. It's also good to compare it with the movie. Saoirse Ronan is so compelling and sympathetic that it's hard to see the hard edge of the novel and much easier to see Miss Kelly as the easy villain. The film also gives us a satisfying, romantic ending. I wonder what Toibin makes of it?

I remember loving Colm Toibin's Brooklyn the first time I read it (in early 2010 I think, when it won the Costa Prize). I also thought last year's film adaption was fantastic. I was sorry then that thirty pages in to my reread I felt underwhelmed. It was the familiarity of the story and the simplicity of style and structure that did it: no beautiful prose, no irony, no oomph. That said I'm happy that I stuck with it as many of the the virtues I enjoyed the first time were still satisfying and I discovered more too.

It's easy to admire Toibyn's precise tightly controlled prose - simple but completely free of cliche. The third-person narrative voice is perhaps somewhat peculiar. It describes everything from the point of Eilis Lacey, a young woman growing up in 1950s Ireland, sent to New York for a new life, but it does so without free indirect speech, instead describing Eilis's observations, actions and ideas with spareness and exactitude. The effect is to convey her seriousness and her methods of thinking. If I didn't fully appreciate this aspect of the text on a first reading it was because I was enjoying the close proximity to Eilis's thoughts and feelings and how it gives us access to her empathy and kindness. I loved the pleasure of witnessing her subtle and understated journey of discovery and Toibyn's astuteness, psychological understanding and wisdom. Seeing Eilis carefully consider her options and become braver was lovely to see.

On second reading I was able to appreciate the quietness and precision of tone more fully and this allowed me to see Eilis's passivity. Eilis's fate is often decided by others and by chance. She has few options but goes about her life with admirable determination and delicacy. Toibin's meticulousness in showing her ways of seeing mean that you trust in her character: in the decisions she makes and her estimations of others. This is crucial to achieving a different kind of complexity in the second half of the novel.

In plotting her return to Ireland, Toibin shows the reader how, habit, environment and circumstance shape Eilis's thoughts and decisions: "It occurred to her, as she walked down the aisle with Jim and her mother and joined the well-wishers outside the church, where the weather had brightened, that she was sure that she did not love Tony now. He seemed part of a dream from which she had woken with considerable force some time before, and in this waking time his presence, once so solid, lacked any substance or form" (245). What I first saw with understanding and admiration - Eilis's openness to experience life on her return to Ireland and her romance with Jim, now touches me with a little pinprick of horror and compelling force. To be so sure that she she does not love Tony after she and the reader are so thoroughly convinced of her happiness fifty pages previously is quite a turnaround. Toibin's method, to draw us so close to Eilis so that we trust her view of the world, and to show her as anything but fickle throughout the rest of the novel, now underscores this difficult truth about the seductive ease of routine and day to day existence. It asks us to sympathise too with Eilis's limited experience of life and with the joy of finding sympathy and love with others.

With all that said, this is hardly a revelatory truth, and nor is there much else in the novel that would make me want to read it again. I prefer a writing style with more energy and a structure that poses more questions. Furthermore there is one aspect that vaguely annoys me. Throughout Toibin asks us to see others through Eilis' eyes AND to trust her judgement. She is constantly imagining what others are thinking and feeling but, unless I am missing the obvious, the text provides no signs that she might be wrong. This is a little bit weird and rather unsatisfactory. Structurally it makes us believe in Eilis's sensitivity and in the story she is constructing about her life but more importantly it reinforces that deeply ideological sentiment that we can understand others so simply and completely. And also, isn't it all a bit too nice and safe? I wanted a bit of peril or irony maybe.

So, definitely glad that I read it again, because it forced me to look more closely, and it's still a novel that I will recommend and think of fondly. It's also good to compare it with the movie. Saoirse Ronan is so compelling and sympathetic that it's hard to see the hard edge of the novel and much easier to see Miss Kelly as the easy villain. The film also gives us a satisfying, romantic ending. I wonder what Toibin makes of it?

Wednesday 6 January 2016

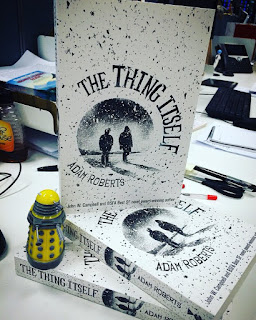

Reading again and The Thing Itself

Oh truth is mutable, saith the sage. Truth is power, not science; or rather, it is science but science is power too. The strong legislate what is true, and after a while we forget that this is whence it came. Our habits of thought are stronger than strait-waistcoats. We walk about with habit-coloured spectacles before our eyes, and see everything as we are accustomed to see it’ [The Thing Itself Adam Roberts]

Reading and watching films are often the main way of navigating my way through life and trying to dislodge those habit-coloured spectacles suffused with ideology and the stories I tell about myself. I mean, sure, people ARE important but sorry, not many of them have the wisdom or the imagination of good art. That doesn't mean I'm a nasty old misanthrope, honest!

Yet, really….how does one navigate through life at all? IS it just like a river? You jump onto a passing log and see where it takes you. Sometimes you stay on for ages; sometimes you hurl yourself on to another one as soon as you can. You have some agency but not half as much as you think? It’s a cliché of course but I do imagine myself like that – generally, scarily, with a hint of Aguirre, Wrath of God in the back of my mind or else on that Mississippi steamboat with Melville’s The Confidence Man. (Or just occasionally I’m on that Houseboat with Cary Grant and Sophia Loren: so many good rivers and boats to conjure up….)

Anyway, I feel like I’ve just hurled myself off my lonely one-person raft and I’m paddling upstream in a canoe, determinedly, trying not to go with the flow, still getting stuck of course, still going back sometimes, but trying. I’m on the lookout for more canoes, villages, towns….people, for fuck’s sake. I’m 44 and feeling, often quite urgently, all the difficult contradictions of mid-life. You could have details but that would be far too uncomfortable for all of us wouldn’t it? Know for now that the autumn was a blur, frantic paddling, lovely relaxed naps whilst tied to the bank – yes we’re still in the metaphor people (!!) – and the odd episode of howling, desperately at the moon after losing my oar.

Good then that I’ve fought to read these last weeks. Good that I’ve launched into such good novels by Adam Roberts, Jeff Vandermeer and various novels on the Costa shortlists though it’s a little hard for me to judge their quality precisely. Good that I'm able to refocus and see a little differently. Reading the first novels after months of not reading is always a particular challenge - about learning to concentrate properly again, thinking critically and attending to form. First up was Adam Roberts’The Thing Itself. I admire his novels a lot and loved his last one Bête. The Thing Itself made me recall the complex, slipstream shenanigans in Christopher Priest’s The Adjacent – and the haunted scientist, Michael Kearny strand of M John Harrison’s Light. But if Priest is smooth and precise and Harrison mordant and challenging then Roberts’ novel is solidly down to earth and enjoyably easy to read even when bursting with pop culture references and high falutin philosophical ideas: comedy and bathos mix with Close Encounters of Third Kind and Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.

The novel begins in the 1986 in Antarctica. Two scientists are processing data in an isolated research station: they are on the lookout for alien life. One is the brilliant Roy Curtius, obsessed with Kant and the Fermi Paradox, and as the reader will discover, all kinds of crazy. The other, saner character is Charles Gardner who will narrate this strand of the novel throughout. Gardner is a familiar voice in a Roberts novel – smart, grumpy, funny, sardonic, embattled. Tonally this first chapter begins like a clever, irreverent comedy written by Steven Moffat but ends up something altogether more hallucinatory and horrific. In subsequent chapters Gardner, his life ruined by his experiences in Antarctica, is compelled to revisit those horrific, life-changing events and face up to the truth. These chapters are full of humour, adventure and it should be said, debates both philosophical and scientific. BUT don’t be put off because Roberts has the ability to make complex ideas understandable AND interesting. Alternating with Gardner’s narrative come a number of strands that focus on seemingly unrelated characters in different times, past and future - the first sees two gay men touring Germany in 1900 for instance and is infused with Nietzsche and HG Wells. At first the links seen tenuous and insubstantial but as the novel progresses you begin to pick up on the deeper thematic and symbolic patterns and the plot elements that connect everything together. It should be said too that these alternate strands are ingenious and deeply satisfying. Here Roberts gives us a variety of voices, evocative of time and place. The effect of these layers is to proffer tension, mystery and revelation. Furthermore they underscore the interrogative nature of the novel and all the debates about the nature of reality between Charles and his interlocutors.

There is much pleasure to be had as always – a Roberts novel is so brilliantly discursive, full of ideas, irony and great prose. And funny – always funny. I also feel ridiculously pleased with myself when I catch a reference – this time quotes from Boorman’s Excalibur and Fowles’ Daniel Martin gave me particular pleasure, perhaps because they are so close to my heart. I’m not sure The Thing Itself is quite as good as Bête, mainly, harshly perhaps, because the central voice of Charles Gardner, is too reminiscent of the central voice in Bête, Graham Penhaligon.

But the reason Roberts’ novels are getting better, and I can’t quite decide if he’ll like me saying this, is twofold. First, for me they live increasingly on the edge of genre in all the best ways – in the gaps and boundaries between sci-fi, fantasy and ‘literary’ fiction – synthesizing, questioning, reaching, blurring and demanding. Secondly, whilst the intellectual challenge is just as fierce, these last two novels feel more human, empathetic, grounded somehow – not sure of the best word (as usual) to use. But I care more, and it feels like he’s not ‘only’ (sorry Adam!) asking me to think about how I deal with philosophy or fiction or science or a million other things but reaching in and with ‘infinite tenderness’ touching my heart as well as my mind.

The Thing Itself is another great novel and will hopefully challenge for prizes, just as Bête should have been on multiple shortlists last year.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)